Walking the Spirit Way: My Journey Through the Ming Tombs

This article follows my personal journey through the Ming Tombs valley near Beijing, where thirteen emperors chose their final resting place among mountains, cypress trees, and solemn stone avenues. I describe how architecture, feng shui, and the natural landscape blend into a single grand design, turning the site into both a historical monument and a living classroom for understanding Chinese views of life, death, and the universe.

Standing at the foot of Tianshou Mountain, about fifty kilometers northwest of Beijing, I often feel that the Ming Tombs are not just a tourist attraction, but a living gateway into the heart of China’s imperial past. This vast valley of stone archways, sacred ways, and underground palaces has become one of my favorite places to introduce to international friends, because here, nature and architecture truly breathe together as one story of power, belief, and beauty.

First impression of the valley

When I arrive with visitors, the first thing I like to do is simply pause at the entrance and let them take in the scale of the valley stretching ahead. The mountains rise gently behind, like a natural screen, while the broad flat basin in front seems carefully prepared as a ceremonial stage. It is easy to forget that this was not built in one moment, but evolved over centuries; yet the layout feels astonishingly unified and deliberate.

Why these tombs matter

The Ming Tombs were established in 1409, after the Ming Dynasty moved its capital to Beijing, and over the next 300 to 600 years thirteen emperors chose to be buried here. Each tomb belongs to a different ruler, yet all follow the same basic principle: nestling into the mountainside, facing the open valley, with the living world stretching outward and the spiritual world embedded in the earth behind. For many of my foreign friends, it is surprising to learn that this is not only the largest imperial tomb complex in China, but also one of the largest in the world in terms of the number of emperors and empresses buried in a single area.

A landscape designed for eternity

As we walk deeper into the site, I like to point out how the Ming architects worked with the terrain instead of fighting against it. The tombs are not scattered randomly; they follow the principles of feng shui, aligning mountains, water, and open space into a grand cosmic order. The valley itself becomes part of the design: a wide ceremonial axis runs through it, while each tomb sits slightly apart, like a respectful guest in a great hall. This careful integration makes the whole area feel both solemn and surprisingly peaceful, as if time has slowed down to match the rhythm of the landscape.

Meeting the emperors by name

One detail that fascinates many visitors is that each tomb has its own name and belongs to a specific emperor. When we look at the map, I introduce them one by one: Changling for Emperor Chengzu, Xianling for Emperor Renzong, Jingling for Emperor Xuanzong, Yuling for Emperor Yingzong, Maoling for Emperor Xianzong, Tailing for Emperor Xiaozong, Kangling for Emperor Wuzong, Yongling for Emperor Shizong, Zhaoling for Emperor Muzong, Dingling for Emperor Shenzong, Qingling for Emperor Guangzong, Deling for Emperor Xizong, and Siling for Emperor Sizong. Together, they are known as the Thirteen Tombs, each representing a chapter in the political, cultural, and personal history of the Ming dynasty.

Walking the Spirit Way

One of the most memorable experiences for many guests is walking along the Shenlu, often called the Spirit Way. This ceremonial avenue is lined with stone statues of officials, generals, and mythical animals that seem to stand guard in silence. As we move between the massive stone lions, camels, and legendary creatures, there is a strong sense of crossing a boundary between the human world and a sacred realm. I always encourage visitors to slow down here, to notice the expressions, the postures, and the way the sculptures echo the curves of the mountains in the distance.

The open tombs you can visit

Although there are thirteen tombs in total, only a few are regularly open to the public. The major ones include Changling, Zhaoling, and Dingling, along with the Spirit Way itself. Changling, the tomb of Emperor Chengzu, often impresses visitors with its grand above‑ground architecture and its sense of balance and dignity. Dingling, on the other hand, is famous for its excavated underground palace, where tourists can descend below the earth and glimpse the stone chambers that once held imperial coffins and treasures. Each site offers a different angle on how the Ming rulers imagined their own eternity.

Recognized as a world treasure

When I introduce the Ming Tombs to foreign friends, many are interested in how the world views this site today. In 2003, the Ming Tombs were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, recognizing them as part of humanity’s shared cultural heritage. This status not only highlights their historical and artistic value, but also brings stronger protection and international attention. In 2011, the area was also designated as a national 5A‑level tourist attraction in China, which is the highest rating for scenic spots, emphasizing its quality of facilities, services, and preservation.

A masterpiece of architecture and nature

Experts from different countries have praised the Ming Tombs as a rare example of perfect harmony between architecture and landscape. The renowned British historian Joseph Needham once described the imperial tombs of China as perhaps the greatest example of integrating built structures with natural scenery, calling the Ming Tombs a true masterpiece. From the main gate tower, one can look across the entire valley and sense how each building has been placed to echo the hills, the sky, and the open land. For many of my guests, this view becomes the moment when they fully understand that the Ming Tombs are not just about death; they are about the living relationship between humans and nature.

The art of movement in space

Another foreign expert, the American urban planner Edmund N. Bacon, admired the tomb complex as one of the most magnificent examples of “motion” in architecture. When leading a tour, I often explain this idea by asking people to pay attention to how they move through the space: passing under gates, crossing courtyards, climbing platforms, and then looking back at the path they have taken. The design guides the body step by step, and in doing so, it also guides the mind from the busy everyday world into a place of reflection and respect. The entire valley becomes a grand narrative told through movement.

Experiencing history on a human scale

Even though the Ming Tombs represent imperial power, what touches many visitors most is the human scale of certain details. The worn steps, the carvings of clouds and dragons, the ancient cypress trees standing silently by the paths—these elements make the past feel close and tangible. As a guide, I like to remind people that the craftsmen, architects, and laborers who built this complex poured their skills and beliefs into every stone. Their work still speaks today, telling stories not only of emperors, but also of ordinary people whose hands shaped this monumental landscape.

How I recommend visiting

When I design a visit for international friends, I usually suggest spending at least half a day in the area. A good route might start with the Spirit Way, continue on to Changling to experience the classic above‑ground structures, and then include Dingling for a glimpse of the underground palace. Comfortable walking shoes are important, as distances can be longer than they appear on the map. I also encourage visitors to bring a bit of curiosity about Chinese concepts such as feng shui and ancestor worship, because understanding these ideas can deepen their appreciation of what they are seeing.

Why the Ming Tombs stay with me

After guiding many groups here, the Ming Tombs have become, for me, a place where the past feels both majestic and intimate. The combination of open sky, gentle mountains, solemn stone avenues, and carefully proportioned halls creates an atmosphere that is powerful but not overwhelming. Many of my foreign friends leave with a new sense of how Chinese people in history viewed life, death, and the universe—as parts of a continuous cycle rather than simple opposites.

Whenever I walk out of the valley and glance back at the distant roofs and mountain silhouettes, I feel that the Ming Tombs are still quietly fulfilling their ancient purpose. They guard the memories of emperors, but they also invite each new visitor to reflect on time, nature, and the legacy of human creativity. Sharing this place in person, and in words, has become one of the most rewarding parts of introducing China to the world.

Recommended

Step-by-Step Guide: How to Apply for Your China Visa in late 2025

Great news for travelers! As of September 30, 2025...

Beijing Travel Guide: Uncover the Heart of China’s Past and Present

As someone who has wandered Beijing’s hutongs, mar...

The Ultimate Guide to China's 30-Day Visa-Free Policy: Are You Eligible?

Great news for global travelers! As of November 20...

“Your Guide to Fast & Easy Payment for Chinese Consulate Services (2025)”

The document explains service fee standards for co...

🇨🇳 Travel Guide — Your Essential Guide to Exploring China

Welcome to China — A Journey of Culture, History &...

My Journey Through Chinese Cuisine: A Symphony of Flavors

When I first set foot in China, I knew food would ...

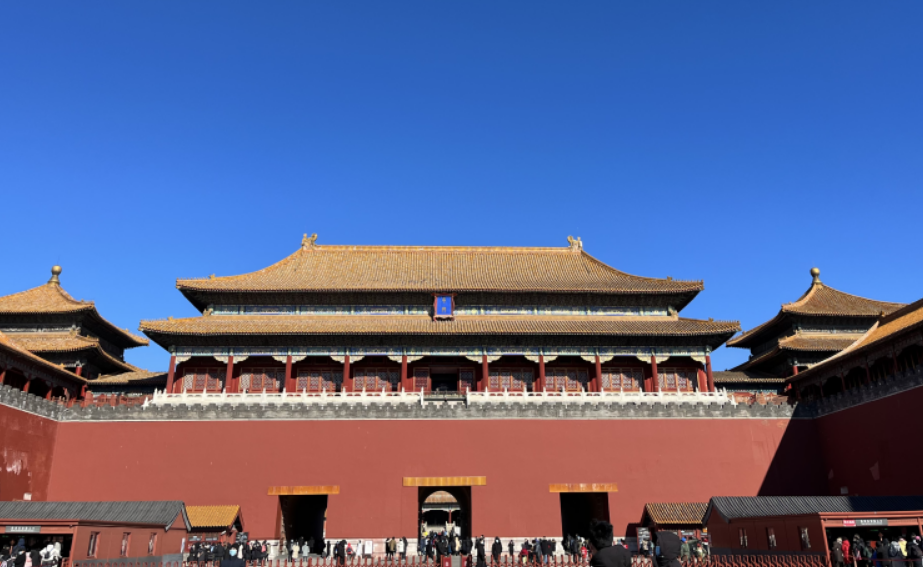

Walking With Emperors: Your Complete Guide to China’s Forbidden City

Step through the crimson gates of Beijing's Palace...

Bite into Shanghai: My Culinary Journey Through Street Stalls and Fine Dining

For me, Shanghai’s food is more than sustenance—it...

A Journey of Taste and Heart: My Wandering Through Chinese Culture

When I clutched the visa emblazoned with the Great...

Shanghai Travel Guide: My Journey Through China’s Dynamic Metropolis

Shanghai isn’t just a financial powerhouse—it’s a ...

No Visa, No Cash, No Worries: The Ultimate Survival Guide to China in 2025

a local travel expert breaks down the revolutionar...