Beijing Food Guide: A Culinary Journey Through History and Flavor

Having spent over a year living in Beijing, I’ve wandered its bustling food streets at dawn, dined in century-old restaurants, and shared home-cooked meals with local families.

Having spent over a year living in Beijing, I’ve wandered its bustling food streets at dawn, dined in century-old restaurants, and shared home-cooked meals with local families. What strikes me most about Beijing’s cuisine is how it tells the story of the city itself—imperial grandeur in every slice of Peking duck, working-class resilience in a crispy jianbing, and regional diversity in a bowl of spicy Sichuan noodles. This guide isn’t just a list of dishes; it’s a roadmap to understanding Beijing through its flavors. From iconic classics to hidden gems, let’s dive into the culinary heart of China’s capital.

1. Imperial Classics: Dishes Fit for Emperors

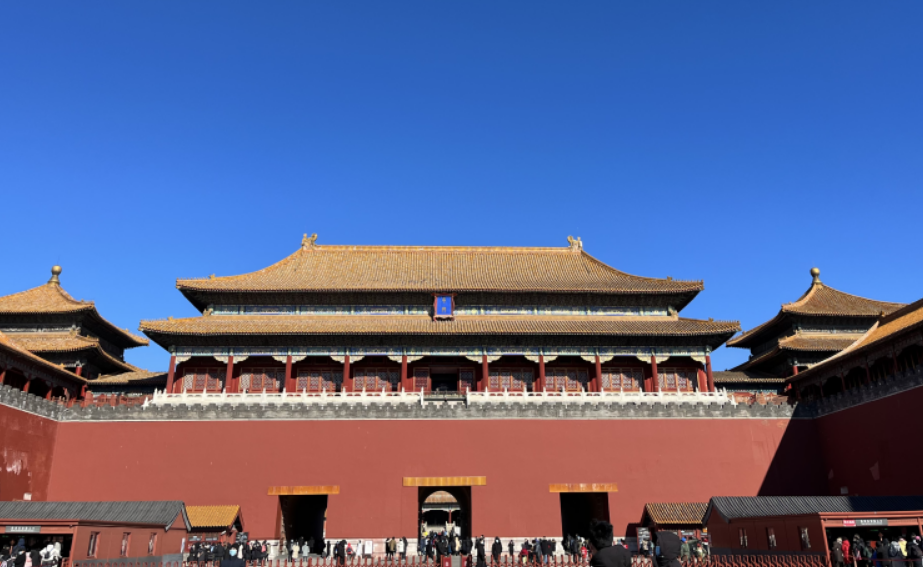

Beijing’s imperial cuisine (yu shi cai) was born in the Forbidden City, where royal chefs spent centuries perfecting dishes that balanced nutrition, aesthetics, and symbolism. These dishes aren’t just delicious—they’re pieces of history, designed to impress both visually and gastronomically. As I sat in a restaurant overlooking the Forbidden City’s golden rooftops, a chef once told me, “Imperial food is about respect—for ingredients, for tradition, and for the diner.” That respect shines through in every bite.

Peking Duck: The Crown Jewel of Beijing Cuisine

No discussion of Beijing food is complete without Peking duck, and my first experience with it was transformative. I visited Quanjude, founded in 1864 and once a favorite of Qing Dynasty officials. The restaurant’s wood-paneled dining rooms and walls lined with historic photos set the stage for what would be a theatrical meal. A server wheeled a cart to our table, revealing a glistening duck with crisp, amber skin—cooked in a traditional wood-fired oven for exactly 45 minutes. The chef, wearing a white uniform and a tall hat, carved the duck with precision, separating the skin from the meat in thin, even slices.

The proper way to eat it? Take a thin, delicate pancake (made fresh daily), spread a dab of sweet bean sauce, add a slice of skin (crispy enough to crackle), a piece of tender meat, a sprig of scallion, and a strip of cucumber. Roll it up tightly and take a bite—the combination of sweet, savory, crisp, and fresh is unforgettable. Pro tip: Ask for the duck bones to be made into a clear soup, a comforting follow-up to the rich duck. While Quanjude is iconic, I also love Da Dong, a modern take on the classic—their duck is lighter, less greasy, and served with creative accompaniments like honeydew melon.

Beggar’s Chicken: A Dish with a Royal Legend

Legend has it that Beggar’s Chicken (jiaohua ji) was invented by a homeless man who wrapped a stolen chicken in lotus leaves and baked it in clay to hide it from officials. Centuries later, it became a imperial favorite. I tried it at Fangshan Restaurant, located in Beihai Park—once a imperial garden. The dish arrives wrapped in a thick layer of clay, which the server cracks open with a small hammer to reveal lotus leaves steeping in steam. Inside, the chicken is so tender it falls off the bone, infused with the earthy aroma of lotus and the subtle flavor of Chinese wine.

The key to a good Beggar’s Chicken is marination—chefs soak the chicken in a mixture of soy sauce, rice wine, and spices for hours before wrapping it. The clay locks in moisture, while the lotus leaves add a unique fragrance. It’s a hearty, comforting dish, perfect for sharing with friends. Pair it with a plate of stir-fried pea shoots for a fresh contrast.

Lion’s Head Meatballs: Symbolism on a Plate

Lion’s Head Meatballs (shizi tou) are named for their size and shape—large, round meatballs that resemble a lion’s head. They’re a staple of imperial cuisine, often served at banquets to symbolize prosperity. I tasted the best version at Min, a restaurant specializing in Huaiyang cuisine (a regional style that heavily influenced imperial cooking). The meatballs are made with a mix of pork belly and lean pork, chopped by hand (never ground, which makes them too dense) and mixed with water chestnuts for crunch.

They’re braised in a rich brown sauce made with soy sauce, rock sugar, and Shaoxing wine for hours, until the sauce thickens and coats the meatballs. Each bite is juicy and flavorful, with the water chestnuts adding a pleasant texture. They’re usually served with bok choy, which soaks up the savory sauce. I was told that imperial chefs would sometimes shape the meatballs with “manes” made of shredded pork, making them look even more like lions—though modern versions are simpler.

2. Street Food: The Soul of Beijing’s Daily Life

While imperial cuisine tells the story of Beijing’s rulers, street food tells the story of its people. Wander any hutong (narrow alleyway) at breakfast time, and you’ll be greeted by the smell of frying jianbing, steaming baozi, and simmering douzhi. These dishes are cheap, convenient, and full of flavor—created by working-class Beijingers to fuel their days. I’ve spent many mornings hopping from stall to stall, chatting with vendors who’ve been serving the same recipes for decades. “Street food is about honesty,” one jianbing vendor told me. “You can’t hide bad ingredients when you’re cooking right in front of people.”

Jianbing: Beijing’s Favorite Breakfast Crepe

Jianbing is the ultimate Beijing street food—every local has a favorite stall, and arguments about which one is best are common. I found mine near my hutong in Dongcheng District, run by an elderly couple who start cooking at 5 a.m. The process is mesmerizing: the vendor pours a thin batter of mung bean and wheat flour onto a hot griddle, spreads it into a circle with a wooden spatula, and cracks an egg on top, mixing it into the batter. They add a sprinkle of scallions, cilantro, and sesame seeds, then flip the crepe to cook the other side.

Next comes the crispy “you tiao” (fried dough stick), placed on top of the crepe to add crunch. The vendor smears a thin layer of sweet bean sauce and a dash of spicy sauce (optional) before folding the crepe into a neat packet. It’s hot, crispy, and savory—perfect for eating on the go. A jianbing costs about 8 yuan (around $1.20), making it one of the best food deals in the city. Avoid tourist-heavy areas like Wangfujing—look for stalls where locals are lining up.

Baozi: Steamed Buns of Comfort

Baozi (steamed buns) are a breakfast staple in Beijing, and I’ve tried every variety—pork, beef, vegetable, sweet red bean, and even salted egg yolk. My go-to spot is a tiny stall near Guozijian Street, where the baozi are steamed in bamboo baskets and sold hot off the stove. The pork baozi (zhurou bao) are the most popular: the filling is a mix of ground pork, ginger, garlic, and soy sauce, with a juicy broth that bursts in your mouth when you bite into it.

Pro tip: Let the baozi cool for a minute before eating, or you’ll burn your tongue on the broth! The vegetable baozi (caibao) are equally delicious, filled with cabbage, mushrooms, and vermicelli noodles. For a sweet treat, try the red bean baozi (hongdou bao), with a smooth, sweet red bean paste filling. A bag of four baozi costs about 10 yuan, making it a filling breakfast or snack.

Douzhi: Beijing’s Acquired Taste

Douzhi is a fermented soybean milk soup, and it’s one of Beijing’s most polarizing dishes—locals love it, while tourists often find it challenging. I was skeptical at first, but after trying it at a traditional breakfast shop in Qianmen, I grew to appreciate it. The soup is a pale gray color, with a sour, earthy flavor. It’s usually served with “youtiao” (fried dough sticks), pickled vegetables (suancai), and “mazhacai” (a spicy pickled mustard green).

The key to enjoying douzhi is to dip the youtiao in the soup and eat it with the pickled vegetables—the sourness of the douzhi balances the saltiness of the pickles, and the youtiao adds crunch. Locals say douzhi is good for digestion and is a great way to start the day. If you’re feeling adventurous, give it a try—just don’t expect to love it on the first bite. A bowl costs about 3 yuan, so it’s worth experimenting with.

Liangpi: Refreshing Noodles for Hot Days

In the sweltering Beijing summer, nothing beats a bowl of liangpi—cold wheat noodles served with a spicy, tangy sauce. I first tried it at a street stall near Shichahai Lake, where the vendor kept the noodles chilled in a bucket of ice water. The noodles are chewy and refreshing, tossed with a sauce made of chili oil, vinegar, soy sauce, garlic, and sesame paste. Toppings include shredded cucumber, bean sprouts, and sometimes shredded chicken or tofu.

What makes a good liangpi is the texture of the noodles—they should be firm but not tough—and the balance of flavors in the sauce. The vendor told me she makes her own chili oil by frying Sichuan peppercorns and star anise in oil, which gives it a deep, complex flavor. A bowl costs about 15 yuan, and it’s the perfect way to cool down on a hot afternoon. I often pair it with a bottle of cold “yanjing” (Beijing beer) for the ultimate summer meal.

3. Regional Flavors: Beijing’s Culinary Melting Pot

As China’s capital, Beijing has attracted people from all over the country, and its food scene reflects this diversity. You can find authentic Sichuan, Cantonese, Shandong, and Xinjiang cuisine on almost every street corner. I’ve spent weekends exploring regional restaurants, and each one feels like a mini-trip to another part of China. “Beijing doesn’t just have its own food—it has all of China’s food,” a friend told me, and I couldn’t agree more.

Sichuan Cuisine: Spicy and Numbing Delights

Sichuan cuisine is one of the most popular regional styles in Beijing, and for good reason—its bold, spicy flavors are addictive. My favorite Sichuan restaurant is Mao Er Lao Ma, a chain known for its hot pot and “mapo tofu.” I tried the mapo tofu first: soft tofu cubes in a spicy, numbing sauce made with Sichuan peppercorns and chili oil, topped with minced pork and green onions. The combination of spicy and numbing (called “ma la”) is unique to Sichuan cuisine, and it’s impossible to stop eating it.

For hot pot, choose a “mandarin duck” pot—one side spicy broth, one side clear broth—so you can try both. The best ingredients to order are beef slices, lamb rolls, tofu skin, and lotus root. Dip the cooked ingredients in a sesame sauce mixture (sesame paste, garlic, cilantro, and vinegar) to balance the spiciness. Mao Er Lao Ma is always crowded, so arrive early or make a reservation. A meal for two costs about 200 yuan.

Cantonese Dim Sum: Elegant Bites for Brunch

Cantonese dim sum is a favorite for weekend brunch in Beijing, and I love going to Tim Ho Wan, a Michelin-starred chain from Hong Kong. The restaurant is small and bustling, with servers pushing carts loaded with steaming baskets of dim sum. My must-try dishes include har gow (shrimp dumplings)—translucent wrappers filled with plump shrimp—and siu mai (pork and shrimp dumplings) topped with a dot of fish roe.

Other highlights are char siu bao (barbecue pork buns) with sweet, sticky filling, and cheung fun (rice noodle rolls) filled with shrimp or barbecue pork. Wash it all down with a pot of jasmine tea, which helps cut through the richness. Dim sum is meant to be shared, so go with a group and order a variety of dishes. A brunch for four costs about 300 yuan—worth it for the quality.

Xinjiang Cuisine: Grilled Meats and Naan

Xinjiang cuisine, from China’s northwest, is all about bold, smoky flavors—perfect for meat lovers. I frequent a Xinjiang restaurant near Wudaokou, run by a family from Urumqi. The star dish is “kao yang rou” (grilled lamb skewers), marinated in cumin, chili powder, and garlic, then grilled over charcoal. The lamb is tender and juicy, with a smoky, spicy flavor that’s irresistible. I usually order a dozen skewers, along with a plate of “laghman” (hand-pulled noodles) in a tomato-based sauce with vegetables and lamb.

Don’t miss the “xinjiang naan”—a large, flat bread baked in a clay oven, sprinkled with sesame seeds. It’s perfect for sopping up the sauce from the laghman or eating with the grilled skewers. For dessert, try “pawala” (a sweet rice pudding) with raisins and nuts. The restaurant has a lively atmosphere, with traditional Xinjiang music playing in the background. A meal for two costs about 150 yuan.

4. Desserts and Snacks: Sweet Endings to Every Meal

Beijing’s desserts and snacks are often overlooked, but they’re just as delicious as the main dishes. Many are traditional, dating back centuries, while others are modern twists on classic flavors. I’ve a sweet tooth, so I’ve spent a lot of time exploring Beijing’s dessert scene—from old-fashioned candy stores to trendy cafes.

Tanghulu: Candied Fruit on a Stick

Tanghulu is one of Beijing’s most iconic snacks—fresh fruit (usually hawthorn berries) dipped in hot sugar syrup, then allowed to harden into a crispy shell. I buy it from a stall near Tiananmen Square, where the vendor arranges the tanghulu in a pyramid shape, glistening in the sun. The combination of sweet, crispy sugar and tart hawthorn is perfect—sweet enough to satisfy a craving, but not too cloying.

In recent years, vendors have started using other fruits, like strawberries, grapes, and even oranges, but the classic hawthorn version is still the best. Tanghulu is especially popular in winter, when the cold weather makes the sugar shell extra crispy. A stick costs about 10 yuan, and it’s a great snack for walking around the city.

Douhua: Silky Tofu Pudding

Douhua is a silky tofu pudding, served either sweet or savory. I prefer the sweet version, which I get at a small shop in Nanluoguxiang hutong. The douhua is smooth and creamy, like custard, topped with a sweet syrup made from rock sugar and osmanthus flowers. Sometimes it’s served with red bean paste or lotus seeds for extra flavor.

The savory version is popular in northern China, served with soy sauce, chili oil, and scallions, but I find the sweet version more refreshing. Douhua is a popular dessert in summer, but it’s also enjoyed in winter as a warm treat. A bowl costs about 8 yuan, and it’s the perfect way to end a meal.

Mahua: Fried Dough Twists

Mahua are twisted fried dough sticks, similar to youtiao but sweeter and more flavorful. I buy them from a traditional bakery near Qianmen, where they’re made fresh throughout the day. The dough is twisted into intricate shapes, then fried until golden and crispy. They’re slightly sweet, with a hint of sesame, and they’re perfect for snacking on the go.

Mahua come in different sizes—small ones for eating as a snack, and large ones that are given as gifts during festivals. I often buy a bag to take with me on day trips, as they’re portable and filling. A bag of small mahua costs about 10 yuan.

5. Where to Eat: From Street Stalls to Fine Dining

Beijing has restaurants for every budget and taste—from hole-in-the-wall street stalls to Michelin-starred fine dining. Here are my top recommendations, based on my own experiences:

Street Food Hotspots

Nanluoguxiang: A popular hutong with trendy cafes and street food stalls. Try the jianbing at the stall near the north entrance and the liangpi at the middle of the alley.

Qianmen Street: A historic street with traditional food stalls. Don’t miss the tanghulu and mahua.

Shichahai Night Market: Open in the evenings, this market has a variety of street food, from grilled skewers to douzhi.

Imperial and Classic Restaurants

Quanjude: Iconic for Peking duck. The Qianmen branch is the oldest and most historic.

Fangshan Restaurant: Located in Beihai Park, perfect for Beggar’s Chicken and other imperial dishes.

Min: Specializes in Huaiyang cuisine, including Lion’s Head Meatballs.

Regional Restaurants

Mao Er Lao Ma: Great for Sichuan hot pot and mapo tofu. The Chaoyang branch is spacious and modern.

Tim Ho Wan: Michelin-starred Cantonese dim sum. The Xinyang Road branch is less crowded than the downtown locations.

Xinjiang Restaurant (Urumqi Flavor): Near Wudaokou, serving authentic grilled lamb skewers and laghman.

Dessert Shops

Old Beijing Candy Store: Near Wangfujing, sells traditional candies and snacks like mahua and tanghulu.

Nanluoguxiang Douhua Shop: A small shop with silky sweet douhua.

6. Practical Tips for Eating in Beijing

Language and Ordering

Most street vendors and small restaurants don’t speak English, but you can use translation apps like WeChat Translate or Google Translate. Many menus have pictures, so you can point to what you want. Learn a few basic phrases: “wo yao yi fen jianbing” (I want one jianbing), “bu yao la” (not spicy), and “duo shao qian” (how much is it).

Payment

Almost all restaurants and stalls accept Alipay and WeChat Pay—link your credit card to these apps for easy payment. Carry cash for small street stalls, especially in hutongs, as some don’t have digital payment.

Etiquette

When eating with others, it’s polite to order more dishes than people, so everyone can try a variety. Use chopsticks properly—don’t stick them upright in your rice (it’s considered bad luck) and don’t wave them around. It’s okay to slurp noodles—locals see it as a sign that you’re enjoying the food.

Best Time to Eat

Breakfast is usually served from 6 a.m. to 9 a.m., lunch from 11:30 a.m. to 2 p.m., and dinner from 5:30 p.m. to 9 p.m. Street food stalls are busiest during breakfast and dinner. For dim sum, go between 9 a.m. and 11 a.m. to avoid crowds.

Final Thoughts

Eating in Beijing is more than just fueling your body—it’s a cultural experience. Every dish has a story, every vendor has a tradition, and every meal is a chance to connect with the city and its people. Whether you’re biting into a crispy jianbing on a hutong corner or savoring Peking duck in a historic restaurant, you’re tasting the heart of Beijing.

As I prepare to leave Beijing, I know I’ll miss the food most of all—the way the smell of jianbing wakes me up in the morning, the warmth of a bowl of douhua on a cold day, and the laughter of friends sharing a hot pot. Beijing’s food isn’t just delicious—it’s memorable. So when you visit, don’t be afraid to try new things, wander off the beaten path, and let your taste buds guide you. You won’t be disappointed.

Corresponding Image Suggestions (with Descriptions for Generation)

Peking Duck Carving Ceremony: A chef in a white uniform carving a glistening Peking duck tableside, with thin pancakes and accompaniments arranged on a porcelain plate. The background shows a historic restaurant with wooden paneling.

Jianbing Vendor at Dawn: An elderly vendor cooking jianbing on a hot griddle in a hutong, with the first light of day in the background. Steam rises from the griddle, and a line of locals waits patiently.

Beggar’s Chicken Unwrapping: A server cracking open a clay-wrapped Beggar’s Chicken with a hammer, revealing lotus leaves and steam. The dish is on a wooden table in a restaurant overlooking a imperial garden.

Xinjiang Grilled Lamb Skewers: A vendor grilling lamb skewers over charcoal, with cumin and chili powder sprinkled on top. The stall is in a busy night market, with neon lights in the background.

Dim Sum Cart in a Restaurant: A server pushing a dim sum cart loaded with bamboo baskets of har gow and siu mai. The restaurant is bustling with diners, and jasmine tea pots are on every table.

Tanghulu Stall: A vendor arranging tanghulu (candied hawthorn berries) in a pyramid shape. The stall is on a historic street, with red lanterns hanging above.

Sichuan Hot Pot Feast: A “mandarin duck” hot pot on a table, with beef slices, lamb rolls, and vegetables arranged around it. Diners are dipping ingredients into the broth, and sesame sauce bowls are nearby.

Sweet Douhua Bowl: A bowl of silky white douhua topped with osmanthus syrup and red bean paste, placed on a wooden table in a small hutong shop.

Lion’s Head Meatballs: Large meatballs braised in brown sauce, served with bok choy on a white plate. The background shows a elegant restaurant with traditional Chinese decor.

Nanluoguxiang Street Food Scene: A busy hutong with street food stalls on both sides. Locals and tourists are eating jianbing and liangpi, and red lanterns line the alley.

Recommended

“Your Guide to Fast & Easy Payment for Chinese Consulate Services (2025)”

The document explains service fee standards for co...

Beijing Transportation Guide: Navigate the Capital Like a Local

During my two years living and working in Beijing,...

Expert Guide: Mastering Mobile Payments in China (2025 Edition)

Below is an English guide designed for your intern...

Best Places to Visit in China: My Journey Through History, Nature, and Modernity

Over the past five years, I’ve traveled to more th...

Walking the Spirit Way: My Journey Through the Ming Tombs

This article follows my personal journey through t...

A Journey of Taste and Heart: My Wandering Through Chinese Culture

When I clutched the visa emblazoned with the Great...

Shanghai Travel Guide: My Journey Through China’s Dynamic Metropolis

Shanghai isn’t just a financial powerhouse—it’s a ...

No Visa, No Cash, No Worries: The Ultimate Survival Guide to China in 2025

a local travel expert breaks down the revolutionar...

Step-by-Step Guide: How to Apply for Your China Visa in late 2025

Great news for travelers! As of September 30, 2025...

Bite into Shanghai: My Culinary Journey Through Street Stalls and Fine Dining

For me, Shanghai’s food is more than sustenance—it...

China Travel Tips: My Love Letter to the Middle Kingdom After Dozens of Trips

After 20+ trips across China, I’m spilling all my ...

Walking With Emperors: Your Complete Guide to China’s Forbidden City

Step through the crimson gates of Beijing's Palace...