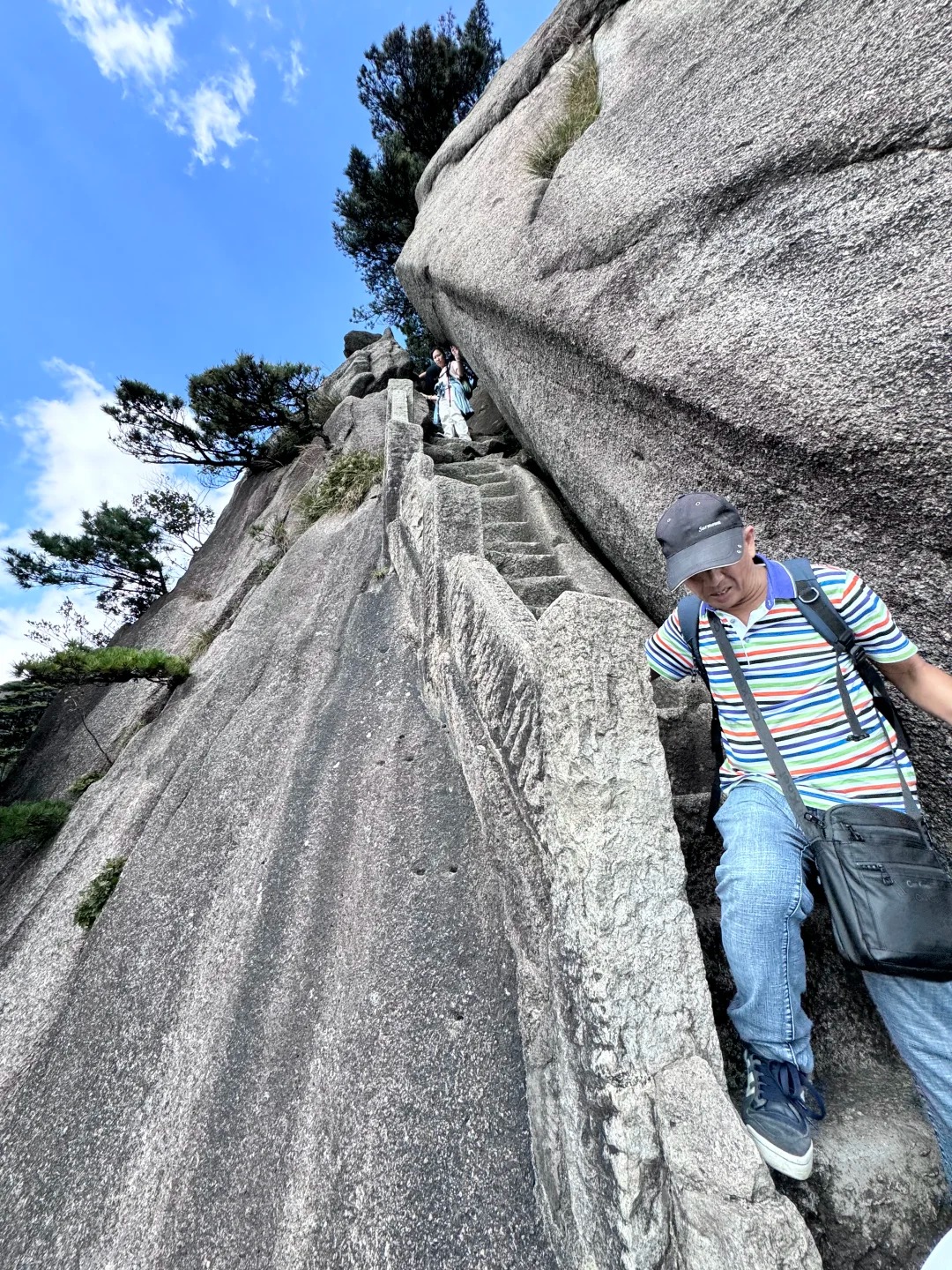

The first breath of air at the foot of Huangshan Scenic Area hit me like a cool, pine-scented hug. It was early autumn, and a thin mist clung to the mountain slopes, blurring the line between rock and sky—exactly the kind of scene I’d seen in old Chinese scrolls, but nothing prepares you for the way it wraps around you, quiet and alive. I laced up my boots and started up the stone steps, their edges worn smooth by centuries of footsteps, and let the sound of crickets and rustling pine needles drown out the last traces of city noise in my head.

Everyone talks about Huangshan’s “four wonders,” but until you stand in front of a Huangshan pine, you can’t grasp what “strange” really means. These aren’t the straight, proud pines of other mountains—they twist and lean, their roots gnawing into cracks in the granite like they’re clinging to the rock for dear life. The Welcoming Pine, that iconic symbol of Huangshan, was my first stop. It’s stood at Jade Screen Peak for over 800 years, its lower branches stretching out like a host’s outstretched arms, and as I stood there, I noticed the way its needles glinted gold in the sunlight, as if it’s been collecting warmth to share with every visitor. An old local guide passing by told me the pine had survived three major storms in the last century alone. “It’s not just a tree,” he said, patting the trunk gently. “It’s a friend of the mountain.”

As I climbed higher, the mist lifted just enough to reveal the grotesque rocks, and suddenly the names made sense. There’s the “Flying Stone,” perched on a ledge so precariously that it looks like a giant tossed it there and forgot to catch it. I sat on a nearby boulder and watched a group of kids pointing at it, making up stories about gods and giants, and realized that’s the magic of these rocks—they don’t just exist; they invite you to imagine. A middle-aged couple from Shanghai sat down next to me, and we chatted about how the rock had looked different when they visited 20 years ago, the mist shifting its shape every time. That’s the thing about Huangshan: it’s never the same twice.

By noon, I reached the top of Lotus Peak, the highest point in the scenic area, and gasped. Below me, the mist had settled into a sea of clouds, rolling and billowing like white waves. Every now and then, a gust of wind would part the clouds, revealing a peak poking through like a tiny island. I pulled out a thermos of hot tea I’d brought from the hotel and sipped it slowly, letting the view sink in. A photographer from Germany was set up nearby, his camera clicking nonstop. “I’ve waited five years to see this,” he said, not taking his eye off the viewfinder. “Worth every minute.” I nodded—words felt unnecessary here.

By late afternoon, my legs were screaming, so I headed to the hot springs area, a 20-minute walk from the peak. The hot springs here aren’t fancy—just simple stone pools filled with mineral-rich water that smells faintly of sulfur. I slipped off my shoes and lowered myself into the warm water, and felt every ache in my muscles melt away. Looking up, I could see the mountains towering above, their tops still touched by sunlight, and listened to the sound of a small stream trickling nearby. A local elder soaking next to me explained that the water comes from deep within the mountain, heated by the earth’s core. “Good for the bones,” he said, grinning. I stayed until the sun dipped below the peaks, the water turning golden in the fading light.

The descent was slower, but I’m glad I took my time. The sunset painted the sky in hues of orange and pink, turning the pine trees into silhouettes and gilding the edges of the rocks. I passed a small temple tucked into a hollow, its red walls glowing in the dusk, and stopped to light a stick of incense. Inside, an old monk was chanting softly, his voice mixing with the sound of wind chimes. I didn’t understand the words, but the peace of the moment wrapped around me like a blanket.

One of the best surprises of the day was the food. Near the entrance of the scenic area, a small stall run by an elderly woman sold dried mushrooms and bamboo shoots, all picked that morning. She offered me a piece of dried mushroom to taste—chewy, earthy, and so full of flavor that I bought a whole bag. “Eat them with rice,” she advised, packing the bag with a paper wrapper printed with a tiny pine tree. Later, I stopped at a family-run restaurant for dinner, where they served stir-fried mountain vegetables and braised tofu, simple dishes made with fresh ingredients that tasted like the mountain itself.

Huangshan Scenic Area isn’t just a place to look at—it’s a place to feel. It’s the way the mist clings to your skin, the way the pines whisper stories of centuries, the way strangers become friends over a shared view. As I left the next morning, I looked back at the mountains, now clear and sharp in the sunlight, and knew I’d carry a piece of that quiet magic with me forever. This isn’t just a scenic spot; it’s a part of China’s soul.