The Gobi Desert does not prepare you for Dunhuang. For hours, the world is a flat, beige expanse, a void under a searing sky. Then, like a mirage made real, the oasis appears—a smudge of green. And at its edge, carved into the dusty cliffs of the Mingsha Shan, lies one of humanity's most profound testaments to faith and art: the Mogao Caves. My visit here was not merely sightseeing; it was a pilgrimage into a silent, painted sanctuary where time, sand, and devotion converged.

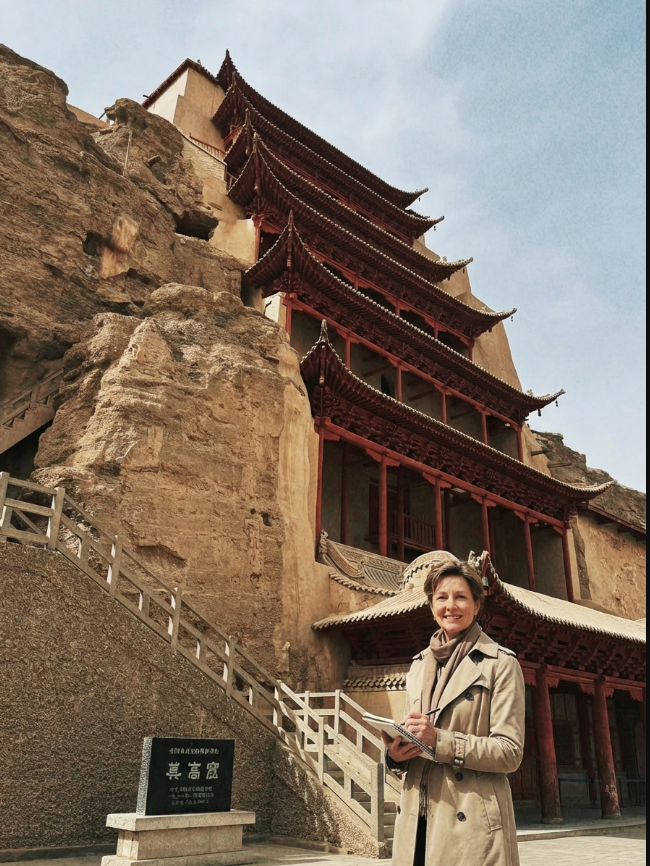

The journey itself is part of the ritual. You cannot wander freely. Access is granted only through meticulously organized guided tours, a necessary measure to protect the fragile atmosphere within the caves. After a brief introduction at the excellent visitor center, my small group was assigned a guide, a scholar whose soft voice held palpable reverence. We boarded a shuttle, trundling across the desert floor toward that unassuming line of cliff face, pockmarked with hundreds of sealed doors.

Stepping from the Gobi's glare into the first cave was like stepping into another dimension—cool, dark, and thick with the scent of ancient clay and mineral pigments. As my eyes adjusted, the guide's flashlight beam swept across the wall, and a universe exploded into view. A towering Buddha, over 30 meters high, gazed down with eyes of infinite calm, his gilded fingers curled in a mudra of reassurance. The sheer scale in the confined space was dizzying, designed to obliterate the ego and inspire awe. This was Cave 96, the "Nine-Story Buddha," and it served as a breathtaking overture.

But the true magic of Mogao lies in the details, in the thousand narratives unfolding in the flicker of a torchlight. In a smaller cave, we crouched as the beam illuminated a thousand tiny apsaras—celestial musicians—floating across the ceiling. Their scarves seemed to ripple in an eternal breeze, their faces serene, their postures impossibly graceful. On another wall, a detailed mural depicted a Silk Road caravan: Bactrian camels laden with goods, Central Asian merchants in pointed hats, a vibrant snapshot of cosmopolitan exchange from over a millennium ago. The paint, made from ground minerals and precious stones, still glowed with startling blues, greens, and crimsons.

The guide explained the layers of history. Work began in 366 AD, when a monk saw a vision of a thousand golden Buddhas in the cliff light. For a thousand years, through dynasties and turmoil, grottoes were carved and painted by monks, merchants, and pilgrims—a cumulative act of devotion. They are a library of Buddhist thought, a gallery of evolving artistic styles from the Northern Wei's ethereal figures to the Tang dynasty's voluptuous realism.

My most haunting moment came in a cave depicting the parinirvana—the final passing—of the Buddha. The colossal reclining figure filled the space, his expression one of profound peace. Surrounding him, disciples and bodhisattvas displayed raw, individualized grief. In their painted faces, carved over 1,400 years ago, I saw a universal human emotion, a bridge across the centuries that left me breathless.

The existential threat to Mogao is ever-present. The guide spoke not just of art history, but of conservation: of controlling humidity from visitors' breath, of battling the encroaching sand, of the painstaking work to stabilize flaking paint. To be here is to witness a desperate, beautiful race against time.

Emerging back into the desert sunlight was a shock. The silent symphony of color and form was replaced by the wind's whisper over the dunes. I had been in the presence of a masterpiece not of a single artist, but of a millennium of human spirit. The Mogao Caves are more than a China must-see; they are a fragile, radiant heart beating in the desert, a poignant reminder of beauty's fierce will to endure.