Most people see Laoshan Mountain as a day trip from Qingdao—a cable car ride, a photo with the "Laozi" statue, a taste of its mineral water. I came to stay. I rented a simple room in a village nestled in its folds, where roosters, not alarms, marked the dawn. This Laoshan, the one beyond the postcard points, revealed itself not as a scenic area, but as a living, breathing ecosystem of rock, water, and quiet human persistence.

My guide was not a person, but a sound: water. Following it, I left the paved paths. Laoshan's granite core is a sponge, releasing its stored rainfall in countless streams and waterfalls. I found one such thread of water cascading down a mossy cleft behind the Yangkou Fishing Village. Sitting on a sun-warmed boulder, watching village women wash vegetables in the cold, clear flow, I understood the mountain's practical soul. This water quenched thirst, irrigated the famous Laoshan tea bushes on the slopes, and gave the local baozi (steamed buns) their distinctive, sweet lightness. The mountain wasn't just for immortals; it sustained life.

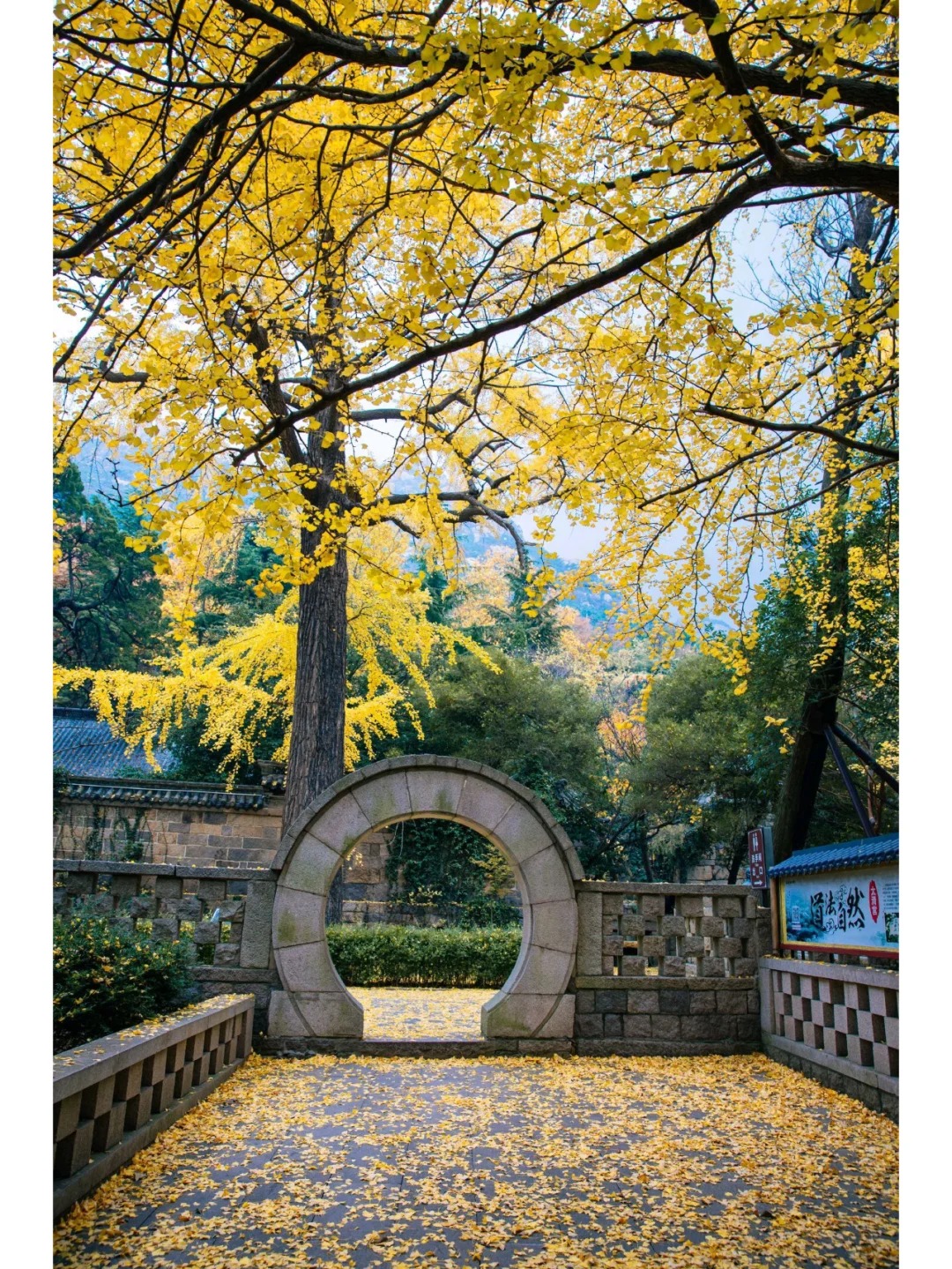

The true heart of the mountain, I discovered, is in its northern, less-visited valleys. In the Nine Waters and Eighteen Pools (Jiushui Bashitan), I spent a whole day hopping from stone to stone along a crystalline stream. Each pool was a world: one, jade-green and deep, reflected overhanging maples; another, shallow and silver, danced over pebbles. The only sounds were the water's endless chatter and the occasional cry of a pheasant. Here, the Taoist concept of ziran (natural spontaneity) was not philosophy, but observable fact. The water found its way without a plan, and the result was flawless beauty.

My search for the "real" Laoshan led me to a crumbling, unnamed hermitage on a western ridge. Only a low stone wall and a single, gnarled pine tree remained. But the view was a revelation: a sweeping panorama of the mountain's serpentine ridges falling away to the distant, shimmering sea. It was a vista earned, not given. Sitting there, sharing an orange with a passing farmer who spoke of his family tending these slopes for generations, I felt the mountain's enduring rhythm. Its story was written not only in imperial poems carved on cliffs but in the calloused hands of those who knew every fold of its land.

I left Laoshan not with a bottle of branded water, but with a pocketful of smooth, grey stones from a stream and the scent of wild tea leaves on my fingers. The mountain’s gift was a reminder that the deepest wonders are often found not at the summit, but in the quiet valleys, following the sound of water, and sharing a moment of silence with its timeless, unassuming spirit.