On a misty morning in Shenyang, I set out to visit Qing Zhaoling Mausoleum, also known as Beiling Park, the final resting place of Huang Taiji, the first emperor of the Qing Dynasty, and his empress Xiaozhuang. As I walked through the main entrance, the noise of the city faded away, replaced by the rustle of pine trees and the chirping of birds. The mausoleum, covering an area of over 160,000 square meters, is one of the largest and best-preserved imperial mausoleums of the Qing Dynasty, and it’s easy to see why it’s been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Unlike the grand and imposing mausoleums of other Chinese dynasties, Qing Zhaoling exudes a sense of peace and serenity, as if nature itself is guarding the emperor’s eternal sleep.

The first thing you notice about Qing Zhaoling is its elaborate entrance archway, a stone structure carved with intricate patterns of dragons, phoenixes, and clouds. The archway stands 12 meters high and 34 meters wide, and every detail is a work of art—from the lifelike dragons coiling around the pillars to the delicate flowers etched into the lintels. As I stood beneath it, looking up at the stone carvings, I was struck by the skill of the ancient craftsmen who created this masterpiece. It’s said that the archway took over 20 years to build, and it’s a fitting introduction to the grandeur and solemnity of the mausoleum beyond.

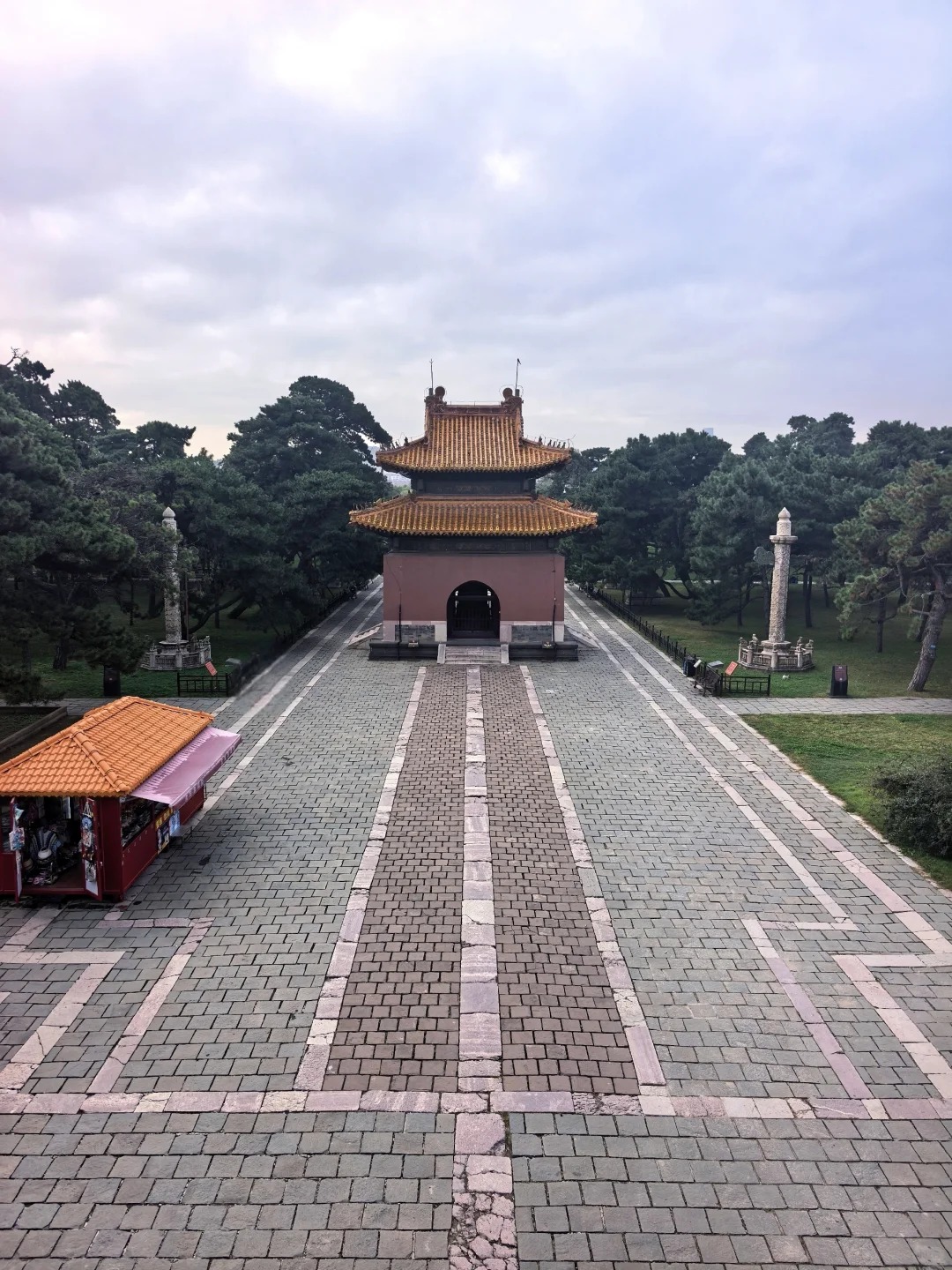

Beyond the archway lies the Sacred Way, a long, straight path lined with stone statues of animals and officials. This is a common feature of Chinese imperial mausoleums, and the statues are meant to guard the emperor’s tomb and show his supreme status. The Sacred Way at Qing Zhaoling is particularly impressive, with 18 pairs of statues—including horses, elephants, lions, camels, and mythical creatures—each carved from a single block of stone. As I walked along the path, I couldn’t help but stop and admire each statue. The horses, with their muscular bodies and pricked ears, looked as if they were ready to gallop at any moment. The elephants, standing tall and majestic, symbolized peace and stability, while the lions, with their fierce expressions, represented power and protection.

One of my favorite statues was that of a mythical qilin, a creature said to appear only during the reign of a virtuous emperor. The qilin’s body is covered with scales, and it has a dragon’s head, a deer’s body, and a fish’s tail. The craftsmanship is so detailed that you can see the individual scales and the gentle expression in its eyes. As I stood there, a local elder told me that touching the qilin’s horn brings good luck, so I reached out and ran my hand over the smooth stone—cold and hard, yet somehow comforting.

At the end of the Sacred Way is the Lingxing Gate, a wooden structure with a green-tiled roof. Beyond this gate lies the inner courtyard of the mausoleum, which includes the Dacheng Hall (Hall of Great Achievement), the Sacrifice Hall, and the tomb itself. The Dacheng Hall is the main building in the inner courtyard, and it was used for imperial sacrifices to Huang Taiji and his empress. The hall’s interior is decorated with red and gold silk, and there are wooden tablets inscribed with the emperor’s posthumous titles on the altar. As I walked inside, the air felt cool and still, and I could almost sense the reverence that once filled the hall during the sacrifice ceremonies.

Behind the Dacheng Hall is the Baocheng, a circular earthen mound that covers the emperor’s tomb. The Baocheng is surrounded by a stone wall, and there are steps leading up to the top, where you can get a panoramic view of the entire mausoleum. As I climbed the steps, the mist began to lift, and I could see the pine trees stretching out in all directions, their green leaves contrasting with the gray stone walls. From the top, the mausoleum looked like a peaceful oasis in the middle of the city, a place where time stands still.

One of the most memorable parts of my visit was watching the locals go about their daily lives in Beiling Park (the area surrounding the mausoleum). Many elderly people come here to practice tai chi, do morning exercises, or play traditional Chinese chess. I saw a group of women dancing to traditional music, their movements graceful and synchronized. There were also families having picnics on the grass, and children flying kites in the square. It was a beautiful blend of ancient history and modern life, and it made me realize that Qing Zhaoling is not just a historical site, but a living part of the city.

I also had the chance to try some local snacks at a small stall near the entrance of the park. The vendor was selling sachima, a traditional Manchu sweet made from fried dough and honey, and shaobing, a savory sesame seed cake. The sachima was crispy and sweet, with a hint of honey, and the shaobing was warm and flaky. As I ate, I watched the people passing by, and I felt a sense of connection to the city and its history. It’s these small, everyday moments that make travel so special.

As the day drew to a close, I made my way back to the main entrance. The mist had completely lifted, and the sun was setting, casting a golden glow over the archway and the stone statues. I stopped for one last look at the mausoleum, and I felt a deep sense of respect for the history and culture that it represents. Qing Zhaoling is more than just a tomb—it’s a symbol of the Qing Dynasty’s power and prosperity, a testament to the skill of ancient craftsmen, and a place where people can connect with the past. If you’re ever in Shenyang, I highly recommend taking the time to visit this beautiful and serene mausoleum. It’s an experience you won’t forget.