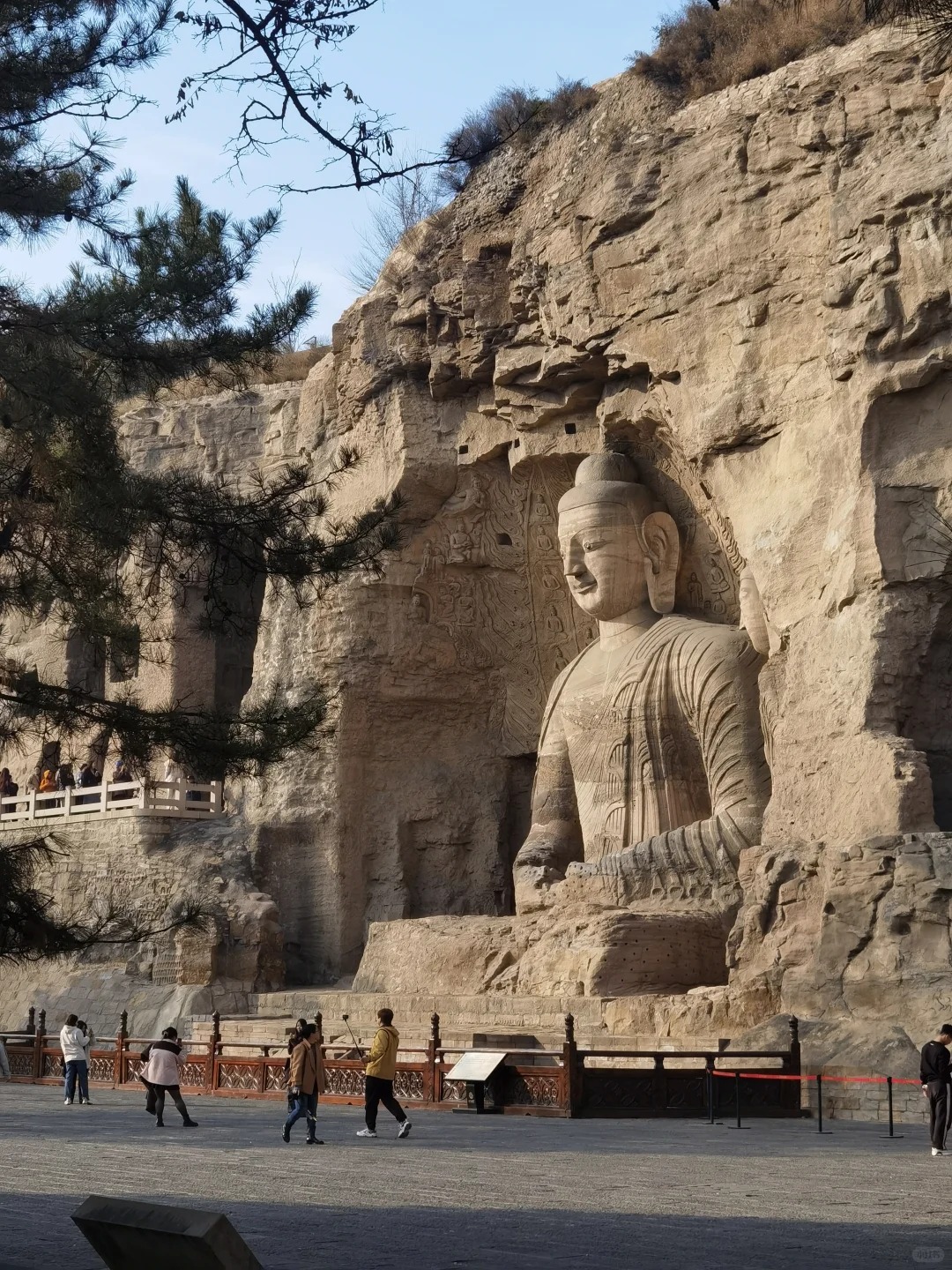

While my first visit to the Yungang Grottoes was about the scale and the overwhelming impact of the site, I returned a second time with a different purpose. I wanted to look closer. I wanted to understand the stories etched into the sandstone. This time, I wasn’t just a tourist checking off a bucket list item; I was a student of art and history, armed with a flashlight and a guidebook, ready to enter the Yungang Caves themselves.

I bypassed the massive Buddha at Cave 20 this time. I wanted to see the smaller details. I headed straight for the cave cluster 5-13, which are often called the “painted caves.” Stepping into Cave 5 was like stepping into a kaleidoscope. The statues here are not just stone; they are canvases. Even after 1,500 years, the paint on the ceilings is vivid. I shone my flashlight on the ceiling and gasped. It was a garden of celestial beings—Apsaras (flying angels) playing lutes, flutes, and drums. The details of their jewelry, the ribbons floating from their shoulders, and the smiles on their faces were so clear they looked fresh.

I spent a good hour just in Cave 6. This cave is a two-story structure known as the Sakyamuni Cave. The carvings here tell the life story of the Buddha. I traced the narrative around the walls: his birth as a prince, his departure from the palace, his enlightenment under the Bodhi tree. The relief work is incredible; the depth perception gives the figures a three-dimensional quality. It felt like watching a silent movie carved in rock. I noticed a small carving of a monkey in the corner, likely a playful addition by an apprentice sculptor. It humanized the entire work for me.

One of the most poignant aspects of the Yungang Caves is the state of preservation. In some of the smaller caves, the erosion is heartbreakingly visible. In Cave 16, I saw a Buddha whose face had been completely worn away by the wind, leaving only a smooth, ghostly oval. It was a powerful reminder of the impermanence of human achievement. I sat in the darkness of the cave, listening to the dripping water and the distant footsteps of other visitors, and felt a deep sadness for the lost art.

I moved to the Cave 12, known for the music. This cave features a three-story wooden facade and a tower. Inside, the walls are covered with images of ancient musical instruments. As a music lover, I was fascinated to see instruments that no longer exist, brought to life in stone. The carvings of the musicians are so dynamic; you can almost see their fingers moving on the strings.

Towards the end of the day, I found myself in a quiet corner of the complex, near Cave 38. This is one of the smaller caves, often ignored by the tour groups. It was empty. Inside, the ceiling is covered in a thousand small Buddhas, each one with a different expression. I sat there, in the semi-darkness, and just looked at them. It felt like they were looking back at me. There was a sense of connection across the centuries—a silent conversation between the carver and me.

This second visit to the Yungang Caves was a different kind of journey. It wasn’t about the grandeur; it was about the intimacy. It was about seeing the brushstrokes of the painters, the chisel marks of the sculptors, and the weathering of time. It reminded me that history is not just a timeline of kings and wars; it is made up of individual hands creating beauty in the dark.

Leaving the caves, I felt a profound sense of gratitude. We are lucky that these masterpieces have survived. If you come to Yungang, don’t just look at the big statues. Go into the caves. Shine a light on the corners. Find the hidden Apsaras. That is where the real magic lives.