"Don't go to Ciqikou," my friend from Chengdu had warned me. "It’s just people, noise, and overpriced squid on a stick."

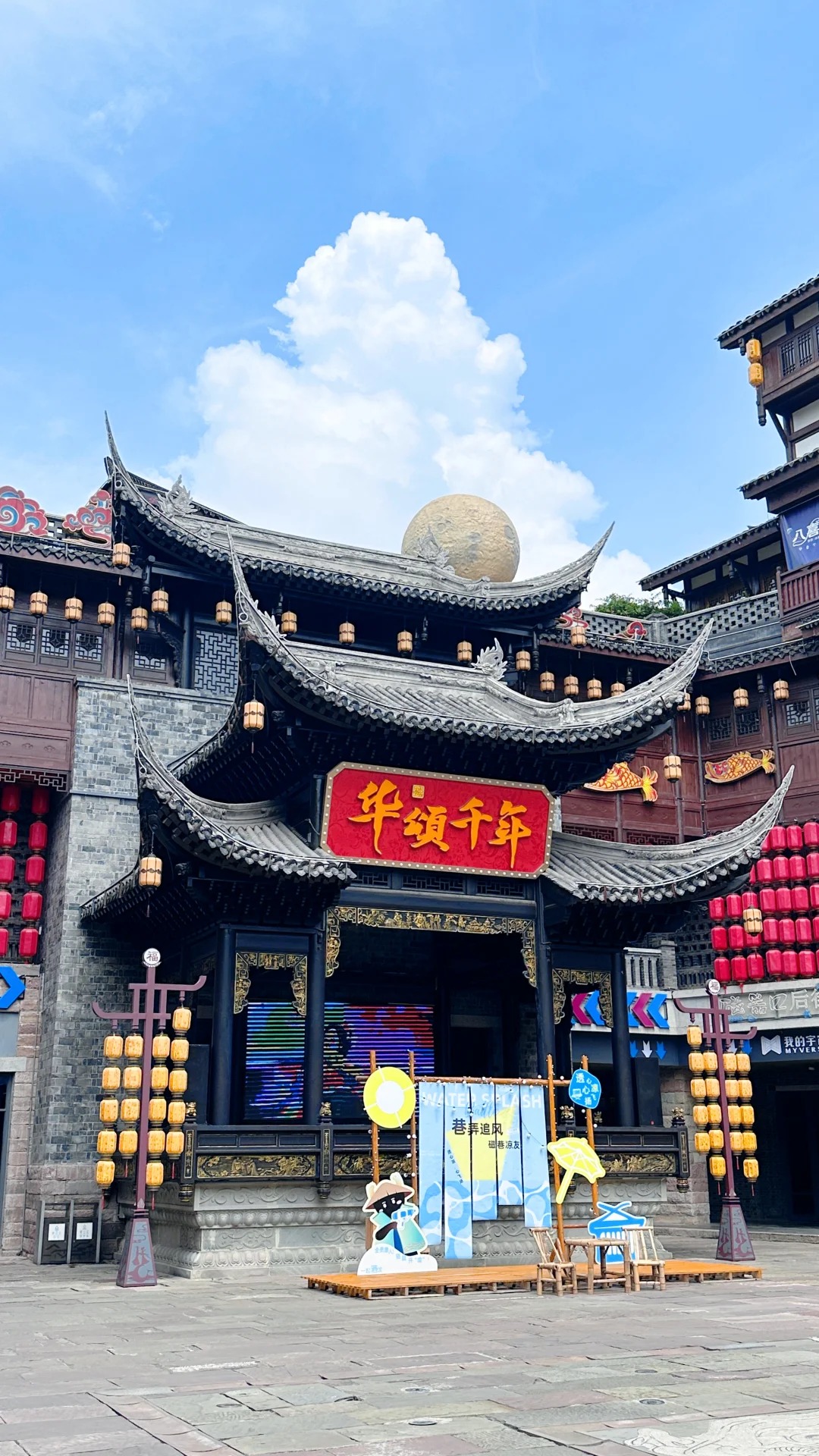

Standing at the main gate of Ciqikou Ancient Town on a Saturday afternoon, I almost believed him. The crowd was a solid wall of bodies. The air vibrated with the sound of a hundred wooden mallets pounding chili powder and peanut brittle, a rhythmic thump-thump-thump that echoed like a frantic heartbeat. The smell was overwhelming—a collision of stinky tofu, frying oil, and sugary syrup.

But I am a stubborn traveler. I don't believe that a place loses its soul just because it gets famous; sometimes, the soul just goes into hiding.

So, instead of flowing with the river of tourists down the main flagstone street, I took a sharp left. I ducked into a narrow alleyway that looked like a dead end. The noise of the main street dropped away instantly, replaced by the sound of my own boots scuffing against uneven stone steps.

This is the secret of Ciqikou: it is not one street; it is a labyrinth.

I climbed higher. The path twisted upwards, away from the river. The buildings here were different. On the main drag, the shops were polished and bright. Here, the wood was dark, weathered by humidity and time. The walls were mossy. I saw an old woman sitting on a bamboo stool, peeling broad beans. She looked up as I passed, her face a map of wrinkles, and gave me a curt nod. No sales pitch, no "hello, look here." Just a nod.

I found myself in a small courtyard cafe called "Lazy Cat." It wasn't really a cafe; it was someone's living room converted into a tea stop. I ordered a Gaiwan tea—green tea with jasmine. The owner, a middle-aged man with a ponytail, brought a thermos of hot water and left me alone.

I sat by the window. From this height, I could look down over the tiled roofs of the town. They cascaded down the hill like grey waves, stopping only at the edge of the Jialing River. In the distance, the modern city of Chongqing loomed, a wall of glass and steel, but up here, time felt sticky and slow.

I sipped the tea. It was bitter at first, then sweet. I thought about the history of this place. A thousand years ago, this was a porcelain port. These stones had been walked on by sailors, merchants, and porters carrying heavy loads of "ci" (porcelain) down to the boats. The chaotic energy of the main street wasn't a modern invention; this place had always been loud. It had always been a place of commerce, shouting, and sweat. The tourists below were just the modern version of the ancient traders.

As the sun began to set, turning the river into a ribbon of gold, I decided to head back down. But first, I wanted to find the Shu Xiu (Embroidery) workshop I had read about.

I found it tucked behind a noisy bar. Inside, it was dead silent. A young woman was bent over a frame, her needle moving faster than my eyes could follow. She was stitching a tiger. The thread was silk, shimmering in the low light. I watched her for twenty minutes. She didn't speak. I didn't speak. In a town famous for its noise, this pocket of absolute focus was mesmerizing. I bought a small handkerchief embroidered with bamboo. It wasn't cheap, but it felt heavy with intention.

My stomach rumbled. I avoided the flashy restaurants with the "face-changing" opera performers out front. Instead, I found a hole-in-the-wall joint where the tables were greasy and the plastic stools were cracked.

"One bowl of Mao Xuewang (duck blood curd in spicy sauce)," I ordered.

When it arrived, it was a cauldron of red oil. Floating in it were slices of eel, spam, duck blood, and tripe. It looked terrifying. I took a bite. The heat was instantaneous, an explosion of numbing peppercorns and searing chili. It wasn't just spicy; it was flavorful, earthy, and rich. I sweated. I drank a cold soy milk. I ate more. This was the taste of the docks—food meant to warm you up and give you energy for hard labor.

I walked out of Ciqikou under the moonlight. The crowds had thinned. The red lanterns were lit, casting a warm glow on the wet stones. I realized my friend was wrong. Ciqikou isn't just a tourist trap. It’s a shell. If you stay on the outside, all you see is the hard, shiny surface. But if you pry it open, if you climb the stairs and sit in the quiet corners, you find the meat of the place. It’s still there, waiting for anyone patient enough to look for it.