My Journey Through the Heart of China

I remember the moment China stopped being a map on my phone and started being a feeling in my chest.

I was standing in the middle of a train station in Beijing. It was cavernous, a cathedral of steel and glass that seemed large enough to hold a small country. The announcement board flipped characters faster than my eyes could track, and around me, thousands of people moved like a singular, flowing river. There was no chaos, only a rhythmic, purposeful current.

For years, I had read about this country. I knew the statistics, the history, the headlines. But standing there, clutching my suitcase, I realized that you cannot learn China; you have to let it wash over you. You have to breathe it in.

This is the story of my journey across the vast, complex, and breathtakingly beautiful land. It is a story of burning legs on ancient walls, burning tongues in spicy cities, and the quiet moments of connection that bridge the gap between "foreigner" and "friend."

The Northern Giants: Dust, Stone, and Emperors

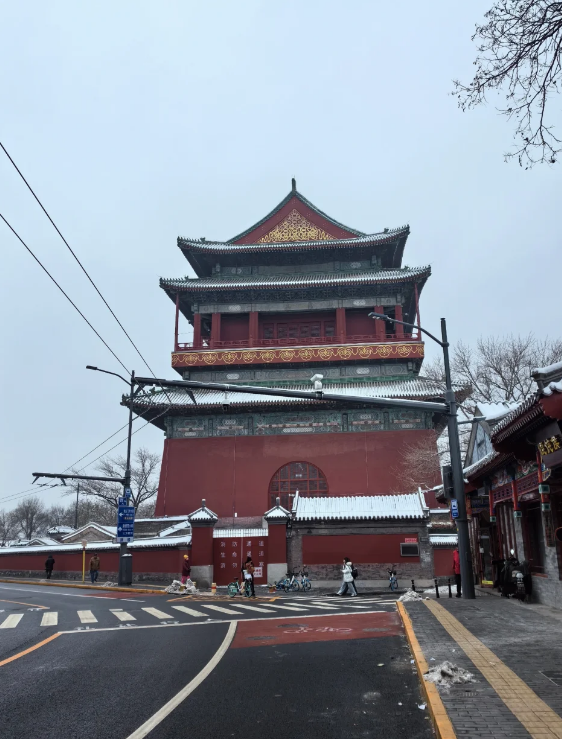

My adventure began in the North, in Beijing. The air here feels different—dry, crisp, and carrying the scent of history mixed with modern ambition.

Everyone tells you to go to the Great Wall, but they don't tell you how it feels to be there alone. I bypassed the crowded sections where tourists flock for cable cars and instead hiked a "wild" section at dawn. The climb was brutal. My breath came in short gasps as I scrambled over loose bricks and twisted roots that had reclaimed the path.

But when I reached the watchtower, silence greeted me.

I stood on the spine of the world. The wall stretched out before me, a gray dragon undulating over the ridges of the mountains, vanishing into the morning mist. It wasn't just a fortification; it was a testament to human will. I ran my hand over the rough, weathered stone. I thought about the soldiers who stood here five hundred years ago, watching the same horizon, shivering in the same wind. I felt incredibly small, a sensation I would feel often in China. It was a humbling start.

Back in the city, I navigated the Hutongs—the ancient alleyways that form the capillaries of old Beijing. This is where the city whispers. I rented a bicycle (a must-do in China) and got lost intentionally.

I remember turning a corner and finding a group of elderly men playing Chinese Chess. They didn't mind my intrusion; in fact, one toothless gentleman waved me over. We didn't speak the same language, but he pantomimed for me to sit. I watched them slam the wooden pieces down with a satisfying clack, shouting in triumph or groaning in defeat. It was raw, unfiltered life. That afternoon, sitting on a stone stool eating a sugar-coated hawthorn stick, I realized that the soul of this empire isn't in the Forbidden City's golden roofs, but here, in the gray brick lanes where life has remained unchanged for generations.

The Spicy Slow-Life: Tea and Fire in the Southwest

Leaving the regal, stoic atmosphere of the North, I boarded a high-speed train.

We need to talk about the trains. If you come from the West, the Chinese high-speed rail is a revelation. I watched the speedometer in the cabin hit 350 kilometers per hour. The landscape outside—wheat fields, factories, rivers, mega-cities—blurred into a smear of color. It was smooth, silent, and frighteningly efficient.

I arrived in Chengdu, and the pace of the movie slowed down instantly.

If Beijing is a marching army, Chengdu is a reclining poet. They say, "Once you come to Chengdu, you never want to leave," and within twenty-four hours, I understood why. The humidity here wraps around you like a warm blanket.

I spent an entire afternoon in a park, sitting in a bamboo chair at a traditional teahouse. This is the church of the locals. I ordered a cup of Jasmine tea, served in a lidded ceramic bowl. Around me, the soundscape was hypnotic: the clicking of Mahjong tiles, the rhythmic scraping of ear-cleaning masters (yes, a distinct local profession!), and the bubbling of boiling water.

But the tranquility is a disguise for the culinary violence that happens at dinner.

I am talking, of course, about Hotpot.

My guide—a local student I met who insisted on showing me "real" food—took me to a place that looked like a warehouse. The air was thick with the smell of tallow, chili, and Sichuan peppercorn.

"Are you brave?" she asked me.

"Try me," I said.

We ordered the spicy broth. When it arrived, it was a bubbling cauldron of red oil, floating with enough dried chilies to incapacitate a large animal. I dipped a slice of tripe in, waited the required seconds, and ate it.

First, the heat. Then, the flavor—garlic, ginger, star anise. And then, the sensation that defines this region: Ma. The numbing tingle of the peppercorn. My lips vibrated. My tongue felt like it had fallen asleep. Sweat beaded on my forehead. It was painful, intense, and absolutely addictive. We ate for hours, sweating and laughing, washing it down with cold soy milk. I learned that night that Chinese food isn't just sustenance; it is a communal sport. It breaks down barriers. You cannot be formal when you are weeping from chili heat together.

Avatar Realized: When Nature Defies Gravity

From the fire of Chengdu, I sought water and stone. I flew to Zhangjiajie, and then later, traveled down to Guilin.

Nothing prepares you for the geography here. In the West, mountains are pyramids. Here, they are pillars.

In Zhangjiajie National Forest Park, I took the Bailong Elevator—a glass box built into the side of a sheer cliff. As we rose, the ground fell away, and suddenly, I was floating among the peaks. These are the quartz-sandstone pillars that inspired the floating mountains in the movie Avatar.

It was a misty day, which I initially thought was bad luck. I was wrong. The mist severed the bases of the pillars from the ground below. They truly looked like they were hovering in the sky. I walked the glass bridge, a terrifying walkway suspended over a canyon. Looking down through the glass floor at the drop beneath my feet required a level of trust in engineering that I wasn't sure I had. But standing there, suspended in the white void, I felt a connection to the traditional ink-wash paintings I had seen in museums. Those paintings aren't stylized exaggerations; they are realism. This landscape actually exists.

Later in the week, I arrived in Guilin to drift down the Li River.

If Zhangjiajie is dramatic, Guilin is poetic. I sat on the deck of a boat, watching the karst mountains drift by. They are softer, rounder, covered in lush green vegetation. I saw fishermen on bamboo rafts, their cormorant birds perched obediently at the bow.

The sun began to set, casting a golden glow over the water. I closed my eyes and listened. The gentle lap of water against the hull, the distant call of a water buffalo, the wind in the bamboo groves. It was a moment of pure, crystalline peace. It felt like I had stepped out of the 21st century and into a poem written a thousand years ago. It was a reminder that despite the skyscrapers and the high-speed trains, the ancient heart of China still beats strong in these valleys.

The Neon Future: A Cyberpunk Dream in Shanghai

My journey ended in the East, where the river meets the sea. Shanghai.

I arrived at night. Driving from the airport, the highway elevated us above the city, and I gasped. It looked like a circuit board come to life.

I headed straight for The Bund. Standing on the promenade, looking across the Huangpu River at the Lujiazui skyline, is a disorienting experience. To my left were the colonial buildings of the 1920s—neoclassical, solid, European. To my right was the future—The Oriental Pearl Tower glowing in pink and purple, the Shanghai Tower twisting into the clouds like a glass DNA strand.

I walked down Nanjing Road, bathed in the glow of neon signs. The energy here is frantic, electric. It’s the sound of money, ambition, and speed.

But my favorite moment in Shanghai wasn't the skyline. It was a morning walk in the Former French Concession. The streets here are lined with London Plane trees that form a green tunnel. The houses are old villas with iron gates and secret gardens.

I found a small coffee shop—not a chain, but a hipster spot that wouldn't look out of place in Brooklyn or Melbourne. I sat there sipping a flat white, watching fashionable young locals walk by. They wore vintage clothes, tapped on the latest smartphones, and walked with a confidence that was mesmerizing.

I started chatting with a local artist sitting next to me. His English was perfect. We talked about jazz, about property prices, about the pressure of modern life.

"Shanghai is a blender," he told me. "We take everything—the West, the East, the old, the new—and we mix it until it becomes something else entirely."

He was right. Shanghai isn't just a Chinese city; it's a global city. It is the proof that this country can hold two opposing thoughts in its head at the same time: deep reverence for the past and a voracious hunger for the future.

On my flight home, I scrolled through my camera roll.

There was the photo of the Great Wall, stark and gray.

The video of the bubbling red hotpot in Chengdu.

The panoramic shot of the green peaks in Guilin.

The selfie with the neon lights of Shanghai reflecting in my sunglasses.

People often ask me, "What is China like?"

And I struggle to answer. Because China isn't one thing. It is a mosaic. It is the silence of a mountain temple and the roar of a subway train. It is the taste of bitter tea and spicy oil. It is a farmer tending his rice paddy and a coder designing AI in a skyscraper.

But mostly, it is the feeling I had when I was lost in that Beijing alleyway, and a stranger offered me a chair. It is a place that, despite its size and its speed, still knows how to make you feel welcome if you are willing to open your heart to it.

My journey is over, but a part of me remains there, sitting on a bamboo chair, listening to the rain fall on a tiled roof, waiting for the next pot of tea to brew.

Go to China. Don't just see it. Feel it.