If you listen closely to the wind in Northwest China, you can still hear them: the bells of camel caravans, the chanting of Buddhist monks, and the clinking of wine cups between merchants who spoke a dozen different tongues. I am a traveler who has always been obsessed with the idea of the "frontier," and nowhere is that frontier more alive, more hauntingly beautiful, than on a China Silk Road tour.

My journey along this ancient artery of civilization was not just a trip across distance, but a trip across time. It stretches from the ancient capital of Xi'an, through the hexagon of the Hexi Corridor, skirting the edges of the Taklamakan Desert, and ending in the exotic oasis of Kashgar. It is a route of dust, gold, and mutton.

Xi’an: Where the Road Begins

Every Silk Road journey must begin in Xi’an (historically Chang’an). Standing atop the Ancient City Wall at sunset, I rented a bicycle. The wall is a massive rectangle of stone, 14 kilometers in circumference, enclosing the heart of the old Tang Dynasty capital. As I cycled, the red lanterns began to glow against the twilight, and I imagined the poets and generals who once walked these ramparts.

But for me, the true soul of Xi’an lies in the Muslim Quarter. It is a sensory overload. The air is thick with the scent of cumin, chili, and charcoal smoke. I navigated through the crushing crowds to find a stall selling Roujiamo (Chinese Hamburger). Unlike the pork version in the rest of China, here it is cured beef, chopped finely and stuffed into a crispy, baked bun. It was savory, salty, and utterly satisfying.

I washed it down with Ice Peak (Bingfeng), a local orange soda that every Xi’an resident grew up drinking. But the highlight was the Yangrou Paomo (Mutton Bread Soak). I sat in a noisy restaurant, breaking a hard, unleavened bread into tiny pieces the size of soybeans—a meditative process that took twenty minutes. The waiter then took my bowl and returned it filled with a rich, milky mutton broth and glass noodles. The bread had soaked up the flavor, becoming soft but chewy. It was a meal designed for travelers, heavy enough to sustain you for a long journey west.

The Hexi Corridor: The Rainbow and the Fort

Leaving the fertile plains, I boarded a high-speed train heading west into Gansu Province. The landscape turned arid, the green fading into ochre and brown. I stopped in Zhangye to see the Danxia Landform.

I have seen many mountains, but Danxia is different. It looks like God spilled his paint box. Stripes of red, yellow, orange, and emerald green ripple across the sandstone hills. Standing on the viewing platform, battered by the desert wind, I felt like I was walking inside an oil painting. It is surreal, a geological miracle that proves nature is the greatest artist.

Further west lies Jiayuguan, the "First Pass Under Heaven." This is the western end of the Ming Dynasty Great Wall. Unlike the stone dragons of Beijing, this fort is built of rammed earth, standing lonely and defiant in the Gobi Desert. I climbed the gate tower and looked out into the vast emptiness beyond. For centuries, this was the end of the known world for the Chinese. To step out that gate was to step into the unknown. I felt a chill, not from the wind, but from the sheer weight of history.

Dunhuang: The Library Cave and the Singing Sands

If Xi’an is the body of the Silk Road, Dunhuang is its soul. This oasis city sits on the edge of the Taklamakan Desert.

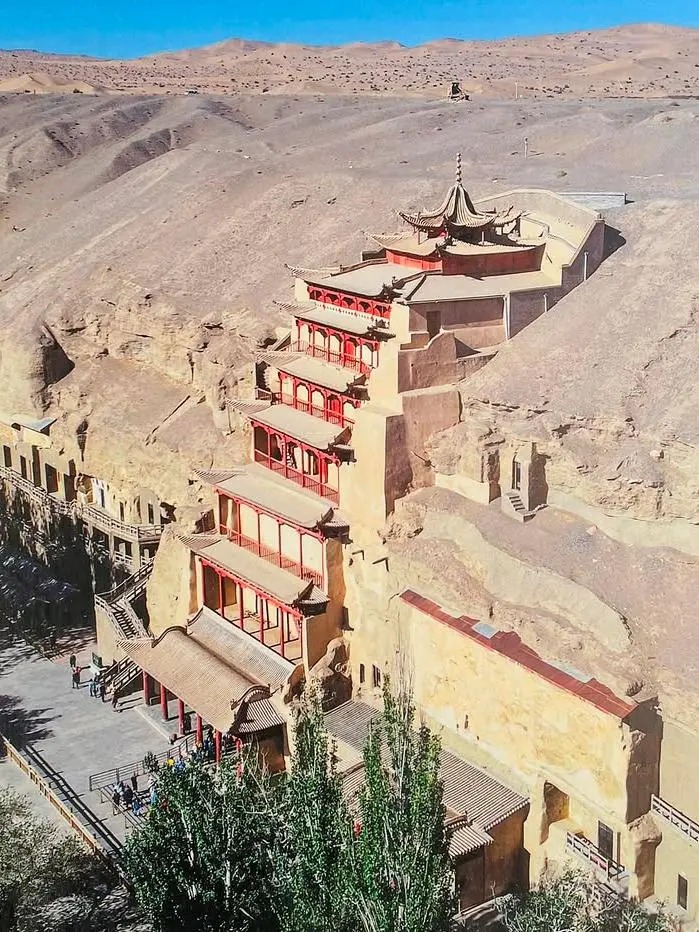

I visited the Mogao Caves, a honeycomb of temples carved into a cliff face over a millennium. Stepping into a cave, guided by the flashlight of a researcher (no cameras allowed), I held my breath. The walls were covered in murals—flying Apsaras (celestial maidens), stories of the Buddha, and portraits of donors from kingdoms long turned to dust. The colors were vibrant, preserved by the dry desert air. It was an art gallery created by faith.

In the late afternoon, I went to the Mingsha Shan (Singing Sand Mountains). The dunes here scream when the wind blows or when you slide down them. I climbed to the top of a massive dune, my boots filling with fine sand. Below me lay the Crescent Moon Spring, a miraculous pool of water in the shape of a crescent moon that has never dried up for thousands of years, surrounded by a small temple.

I sat on the dune ridge until the sun dipped below the horizon, painting the desert in shades of purple and gold. The silence was absolute. I realized then that the desert is not empty; it is full of silence, and that silence speaks louder than any city.

Turpan: The Oven of China

Crossing into Xinjiang, the heat hit me. Turpan is located in a depression below sea level and is known as the "Land of Fire." But it is also the land of grapes.

I walked under the trellises of the Grape Valley, where the temperature was ten degrees cooler. A local Uyghur family invited me into their courtyard. The grandfather, wearing a traditional doppa cap, cut down a bunch of "Mare’s Nipple" grapes—long, green, and impossibly sweet. We sat on colorful carpets, eating grapes and Hami melon, which tasted like pure honey.

He explained the Karez system to me—an ancient underground irrigation system that brings water from the snow-capped mountains to this parched land. "Without water, there is no life," he said. "With water, the desert blooms."

Kashgar: The Living History

The final stop was Kashgar, the westernmost city in China. This is where the Silk Road splits. The Old City of Kashgar is a maze of mud-brick houses, climbing over each other in a chaotic, beautiful dance.

I spent a Sunday at the Livestock Market. It was a scene straight out of the Middle Ages. Thousands of farmers, shepherds, and traders gathered in a dusty lot. Donkeys, sheep, camels, and yaks were bartered with vigorous handshakes hidden inside long sleeves. The air smelled of animal musk and hay.

For lunch, I went to a night market. The smoke of grilling meat was thick. I ordered a Shish Kebab—chunks of lamb the size of a fist, skewered on tamarisk wood and dusted with cumin and salt. It was primal and delicious. I also tried Polu (Pilaf), rice cooked with carrots, raisins, and lamb fat in giant iron cauldrons.

I ended my trip at the Id Kah Mosque square. Elderly men sat on benches, drinking tea and watching the children play. I realized that while the caravans are gone, the spirit of the Silk Road—the exchange of goods, ideas, and smiles—is still very much alive here.

Why You Must Take This Journey

A China Silk Road tour is demanding. It involves long travel days and harsh climates. But it rewards you with the most diverse experiences China has to offer. You start in the heart of Han culture and end in the vibrant world of Central Asia. You see the Great Wall end and the desert begin.

As your guide, I tell you this: Come for the history, but stay for the humanity. Stay for the smile of the grape farmer in Turpan, the silence of the Dunhuang dunes, and the taste of the best lamb you will ever eat. This is a journey that changes you.