Let me tell you about the moment I stopped being a tourist in Lijiang and became a witness. It wasn't at the famous drumming show or the bustling Sifang Street under midday sun. It was in the pre-dawn blue, lost in the maze of the Old Town. The cobblestones, slick with overnight dew, mirrored the fading stars. There was no one. Just me, the gurgle of snowmelt coursing through the ancient stone canals, and the distant, spectral outline of the Jade Dragon Snow Mountain against the lightening sky. The air was cold, thin, and carried the scent of wet wood and yesterday's hearth fires. This was Lijiang exhaling, a private performance before the day's curtain rose.

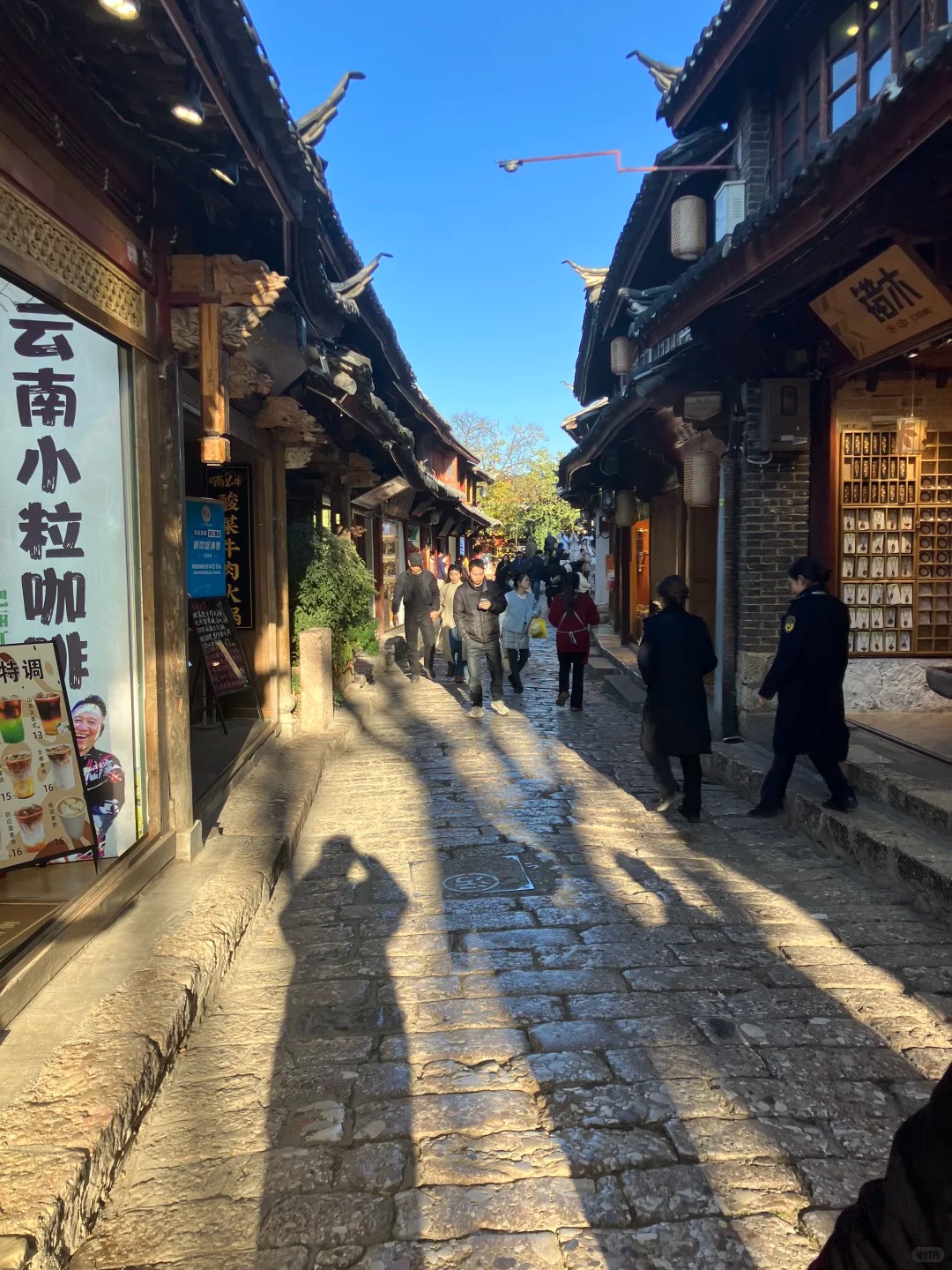

I followed the water's song. These waterways, engineered by the Naxi people centuries ago, are the town's arteries. At dawn, you see their true purpose—not as decoration, but as life. An old woman, her back bent under a traditional (Seven-Star Shawl), emerged from a dark wooden door. Without a glance, she knelt by the canal and began washing a bundle of greens. The scene was timeless. This was how it had always been. The mountain's runoff giving life, the people receiving it with a quiet, practical grace. I bought a from a vendor just sliding his iron griddle over coals. The salty, flaky bread steamed in the chill. Sitting on a worn doorstep, eating with my fingers as the first gold light touched the eaves, I felt an intimacy no guided tour could ever provide.

But Lijiang demands you lift your eyes from its charming alleys. To understand it, you must face the mountain. The road to the Jade Dragon Snow Mountain is a pilgrimage of switchbacks and gasps. At Yak Meadow, 3,500 meters up, the world simplifies. The air is a piercing crystal. The wind carries a voice that feels ancient. Before me, the mountain's main peak, Shanzidou, stabbed the impossibly blue sky, its facets of rock and ice blinding in the sun. Naxi legend reveres this mountain as "Sanduo," a warrior god in white armor, the protector of their people. In that staggering silence, broken only by the wind and the faint chime of a yak's bell, belief felt logical. It wasn't a scenic backdrop; it was a dominant, conscious presence. I was a speck at its feet. My breath plumed in the thin air, a transient offering to its eternal stillness. The headache from the altitude was a small price for this humbling communion.

The descent back to humanity was through sound. That evening, in a modest hall with plain wooden benches, I attended a performance of the Naxi Ancient Music. This is no folkloric spectacle. The musicians, most in their seventies and eighties, shuffled on stage with an air of solemn ceremony. Their instruments—oboe-like "sheng," lutes, dulcimers—were antiques, some reportedly from the Tang Dynasty courts. The music they played, is said to be a requiem. It is slow, haunting, dissonant to an untrained ear, full of spaces and silences that feel heavier than the notes. As the lead musician, a man with a wispy white beard, drew a trembling bow across his "erhu," his eyes were closed, his face a mask of deep

concentration. He wasn't performing for us; he was channeling. He was speaking to ancestors in a language of fading frequencies. In that hall, with dust motes dancing in the stage light, time collapsed. The modern world fell away, and I was listening to the very soul of this place—a soul shaped by trade routes, Himalayan winds, and a deep, animistic reverence for nature. It was melancholic, beautiful, and profoundly real. It was the sound of history breathing.

concentration. He wasn't performing for us; he was channeling. He was speaking to ancestors in a language of fading frequencies. In that hall, with dust motes dancing in the stage light, time collapsed. The modern world fell away, and I was listening to the very soul of this place—a soul shaped by trade routes, Himalayan winds, and a deep, animistic reverence for nature. It was melancholic, beautiful, and profoundly real. It was the sound of history breathing.

Lijiang taught me that the most precious things are often held in the quiet margins. Go to the canals at dawn. Sit with the old men playing chess in the sun. Let the mountain silence you. The postcard-perfect town is a lovely shell, but the true Lijiang lives in the whispered conversations between stone and water, in the gaze of the Naxi elder, and in the last, quavering notes of a song that refuses to die.